I recently had the opportunity to assist curator of dress Judith Clark with the installation of the Washed Up exhibition at the Selfridges department store in London. From a curatorial perspective, it was like playing in the dressing-up box.

I recently had the opportunity to assist curator of dress Judith Clark with the installation of the Washed Up exhibition at the Selfridges department store in London. From a curatorial perspective, it was like playing in the dressing-up box.

Washed Up is Clark’s response to the current “retail activism” taking place at Selfridges, to raise awareness of dwindling fish stocks and the plight of the World’s seas. Events are taking place for the next month to highlight the impact we are having.

Clark aims to use dress as the vehicle to highlight the influence nature, specifically the seas, has on fashion and the way we dress.

I got to dress a mannequin with an 1870s bustle-back dress (that would have been worn for a trip to the sea), to wrestle with a crinoline with a steel frame from the 1850s (that probably would have blown away if you had worn it near the sea’s winds), and a 1920s swimming suit in wool jersey (wet wool. Nice.).

I dressed an Alexander McQueen gown from the Plato’s Atlantis collection (S/S 2010). It was a real mix of eras and themes, and great fun to work on.

But, like most department stores, installation had to take place out of hours; hence, we installed from 11.30pm Monday night to 7.30am Tuesday morn.

I was well and truly washed up by then.

BDW

Another of my recent holiday exhibition highlights, but for very different reasons.

Dior Illustrated: René Gruau and the Line of Beauty at Somerset House on the Strand was a titillating exploration of fashion illustration at its best. And it’s all there in Gruau’s original drawings, covering decades of fashion advertising and charting some of the great social movements of the 20th century. Sex, allure, jutting hip bones, bright white teeth, vermilion lips, emancipation, audacity, an Haute Couture lifestyle. A lifestyle completely out of the reach of most women and men, but one that was easily claimed, if only for a moment, with a whiff of Diorissimo or Eau Sauvage.

What is most interesting is the amount of bleed proof white correcting fluid Gruau used to create The Line of Beauty. Even a great illustrator relied on an artist’s little helper to get the line just so.

Nothing is perfect, I guess.

BDW

Holidays are great things. You have the time to go and see all those exhibitions you’ve had to put off due to families, studies or work. I spent a recent holiday making the most of it, hot-footing it around London’s museums and galleries.

Holidays are great things. You have the time to go and see all those exhibitions you’ve had to put off due to families, studies or work. I spent a recent holiday making the most of it, hot-footing it around London’s museums and galleries.

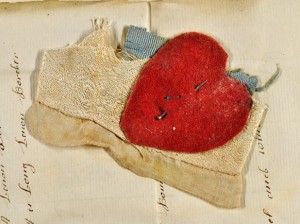

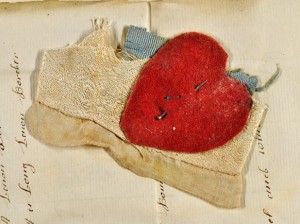

The Foundling Museum’s Threads of Feeling was a reflection on the tokens mothers left with their children when they delivered them to the Foundling Hospital orphanage during the 18th century. A memorable object was pinned to the inventory notes for each child. This was a form of identity for when mothers came to reclaim their children, and was necessary as the Hospital removed any trace of the child’s history once registered – even their names were changed.

Threads of Feeling explored the textiles-based tokens left behind in vast inventories. Embroidered poems urge a child never to give up on their mother returning. Swatches of plain navy wool remind us that, in the 18th century, most children’s clothing was made from the material of their parents’ cast-offs. Vivid ribbons and chintzes, colours still fresh after more than 200 years safely kept from harmful UV rays, are an ironic burst of brightness in an otherwise sad tale. Another irony: this is one of the best resources of 18th Century fabric in the world.

These fabric pieces are a gentle reminder that clothing in the 18th century wasn’t all about the finest silks and embroidery that money could buy, however beautiful the gowns displayed in museums are. The swatches are proof of the harsh reality of everyday living for millions of people who couldn’t afford new clothes, let alone the opportunity to keep their babies. These are the few material artefacts we have that stand testament to the reality of life for the majority of 18th century society.

Sadly, less than 1% of the children were ever collected by their mothers. It was a profoundly moving exhibition, using small scraps of material to tell huge stories.

(Image courtesy of the Foundling Museum, London)

BDW

Those are the spaces that make the difference between a blunt intrusion and a beautiful slice with a subtle knife. The spaces that underscore the intention of the creation, be it object or word, allowing a personal interpretation to take place. They emphasise and delineate the article while allowing space to pause, to feel and interpret the energy that brought forth the creation. It is where inuition lives, it is the part of the world behind the eyes, deep in the soul, in the space between bodies, minds and objects, in the interconnected energies of the universe. Those spaces speak louder than the object, louder than any words. Those spaces are the creation’s body language, the language that cannot deceive.

MBW

Recently finished reading the newly-published autobiography by Yohji Yamamoto, the great Japanese designer. It’s called My Dear Bomb. In it, he talks of the Japanese concept of ma, or the ‘empty gaps in time and space.’

Ma is all about space; it is a pause in a spoken phrase or movement, an interval between two things. It is described as a concept of the recognition of space that the viewer/reader experiences within. In other words, it is an experiential thing – the viewer’s perception has a lot to do with it.

It got me thinking about space within creativity. When we create our garments, objects, stories, whatever, do we consider the spaces in between? How do the pauses and the spaces impact (if they do at all) on our design and the story we are telling?

Any thoughts, anyone?

BDW

A friend (you may have heard me talking of her before) lives, breathes and loves Yohji Yamamoto’s designs. And she looks amazing in everything she wears.

A friend (you may have heard me talking of her before) lives, breathes and loves Yohji Yamamoto’s designs. And she looks amazing in everything she wears.

She recently returned from Hong Kong with a latest purchase that I couldn’t help but grab off her shoulders and photograph. It is a blurry image, and not well composed. But think of it as an image taken in a desperate need to get to know this garment.

It is, simply put, a wide and long scarf with a very plain hood attached to one side half way along the longest side. The image shows the scarf folded in half. The material is woven, not knitted; a fine cloth with some weight, but not too much.

That’s it. Nothing complicated or confusing. And yet, when worn, it looks magical.

BDW

My friend Rosie is researching the eighteenth century mantua that I have raved about for ages in this blog and which you won’t see for a while yet. Patience, our dear readers, patience.

My friend Rosie is researching the eighteenth century mantua that I have raved about for ages in this blog and which you won’t see for a while yet. Patience, our dear readers, patience.

Rosie is a meticulous researcher, and I have learnt so much from working with her and being around her. Her understanding and insights into the dress, eighteenth century embroidery and cloth weaving grows daily.

In Rosie’s hands, embroidery is an art. I have seen her 3-D embroidery for an art installation, and it was captivating. Leaves, embroidered in deep greens, unfurled off the bodice of a gown, curling and twisting, reaching out into space.

The image highlights some of the acetates Rosie has created of the mantua’s bodice. On these acetates is drawn every section of embroidery – where the colour shifts in hue, any damaged areas, indications of any change of embroiderer’s personal style (the number of people who worked on the dress is numerous going by the different styles of stitching).

With these acetates, Rosie slowly unpicks the history of this fine gown. Each stitch reveals something. The scans will help her reveal even more.

It really is enlightening to see the story unfold.

BDW

At the V & A Museum the other day, helping a friend with the scanning of an eighteenth century mantua for her MA research. And then we saw this and it made us laugh.

At the V & A Museum the other day, helping a friend with the scanning of an eighteenth century mantua for her MA research. And then we saw this and it made us laugh.

The dos and the don’ts of the V & A. It was quite a read. It was all there in tab form, ready for us to defend the nation’s prizes. Shonagh (the woman in the photo) and I could now tackle any terrorist, art thief or blackmailer with the flick of a wrist.

BDW

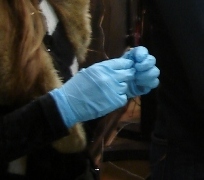

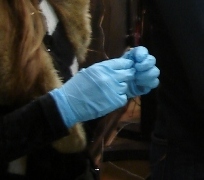

It did feel a little like a violation. Here we were, students of dress curation and history, gingerly coaxing a 1740s (or thereabouts) court mantua into place for each scan of her delicate fibres wearing blue latex gloves.

It did feel a little like a violation. Here we were, students of dress curation and history, gingerly coaxing a 1740s (or thereabouts) court mantua into place for each scan of her delicate fibres wearing blue latex gloves.

Ivory silk satin, shimmering under bright, industrial lights, the field in which a fantasia of flora invades the senses. You could feel the heat of the sun warming explosions of blossoms glinting and swaying in the breeze somewhere in never-never land.

Cornucopia stitched in gold and silver thread, offering up blousy, heavy bulbs ready to spring into life. Chrysanthemums and anenomes growing out of the same branches, reaching for the sky in bright reds and blues, violets and greens.

As we moved the gown for each scan, we had to pick up the minute pieces of the gold and silver thread as they dropped off, the material and embroidery so fragile with age.

And here we were, using blue latex gloves to touch this beauty? Wrong, all wrong.

BDW

My friend researching the mantua asked me to help take it to the Victoria and Albert Museum a few Saturdays ago to have the old gal scanned. Although I had to hand in my MA thesis a week later, there are just some things you have to be involved in, and I wasn’t going to miss this opportunity for the world.

My friend researching the mantua asked me to help take it to the Victoria and Albert Museum a few Saturdays ago to have the old gal scanned. Although I had to hand in my MA thesis a week later, there are just some things you have to be involved in, and I wasn’t going to miss this opportunity for the world.

I can’t show you a picture of the old lady. She’s a bit publicity shy at present. And my friend would kill me if I showed images to the world, as the research is not yet published. The old gal’s reintroduction into society will have to wait a bit.

In the meantime, here’s a photo of the box we used to carry the grand old lady to the museum for the day to have her photo taken. It’s quite pretty too.

BDW

I recently had the opportunity to assist curator of dress Judith Clark with the installation of the Washed Up exhibition at the Selfridges department store in London. From a curatorial perspective, it was like playing in the dressing-up box.

I recently had the opportunity to assist curator of dress Judith Clark with the installation of the Washed Up exhibition at the Selfridges department store in London. From a curatorial perspective, it was like playing in the dressing-up box.